- Home

- Upendranath Ashk

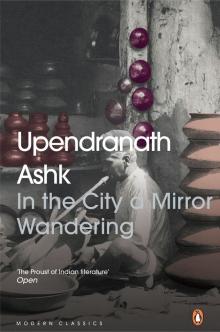

In the City a Mirror Wandering

In the City a Mirror Wandering Read online

UPENDRANATH ASHK

In the City a

Mirror Wandering

Translated from the Hindi

with an Introduction by Daisy Rockwell

PENGUIN BOOKS

CONTENTS

Translator’s Introduction

Author’s Preface

Morning

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

Afternoon

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

Evening

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

Acknowledgements and Dedication

Follow Penguin

Copyright

PENGUIN MODERN CLASSICS

In the City a Mirror Wandering

UPENDRANATH ASHK, 1910–1996, was one of Hindi literature’s best known and most controversial authors. Ashk was born in Jalandhar and spent the early part of his writing career as an Urdu author in Lahore. Encouraged by Premchand, he switched to Hindi, and a few years before Partition, moved to Bombay, Delhi and finally Allahabad in 1948, where he spent the rest of his life. By the time of his death, Ashk’s phenomenally large oeuvre spanned over a hundred volumes of fiction, poetry, memoir, criticism and translation. Ashk is perhaps best known for his six-volume novel cycle, Girti Divarein, or Falling Walls—an intensely detailed chronicle of the travails of a young Punjabi man attempting to become a writer—which has earned the author comparisons to Marcel Proust. Ashk was the recipient of numerous prizes and awards during his lifetime for his masterful portrayal, by turns humorous and remarkably profound, of the everyday lives of ordinary people.

DAISY ROCKWELL is an artist and writer living in northern New England. She paints under the takhallus, or alias, Lapata (Urdu for ‘missing’), and has shown her artwork widely. Rockwell holds a PhD in Hindi literature and has taught Hindi–Urdu and South Asian literature at a number of US universities. Apart from her essays on literature and art, she has written Upendranath Ashk: A Critical Biography, The Little Book of Terror, a book of paintings and essays on the global war on terror, and the novel Taste. She has translated a collection of Ashk’s short stories, Hats and Doctors (published in Penguin Classics), and a widely acclaimed translation of Girti Divarein (published in Penguin Classics as Falling Walls), the first volume of Ashk’s epic novel cycle. Her translation of Bhisham Sahni’s iconic Partition novel Tamas (also published in Penguin Classics) is regarded as the definitive English rendition of that work. Most recently, she has translated Khadija Mastur’s Aangan (published in Penguin Classics as The Women’s Courtyard).

Praise for Falling Walls

‘I envy Daisy Rockwell, who has lived with the Falling Walls series for at least two decades . . . Beguiling . . . Daisy Rockwell’s translation is superb, because it is so unobtrusive. The flavour of Ashk’s Hindi comes through behind the form of the English words, setting this classic free to reach an even larger audience than before’—Nilanjana Roy, Business Standard

‘Falling Walls is a terrific, deeply engrossing read . . . [It] is also a multi-layered portrait of intersecting worlds, with Chetan as the fulcrum. It is about relationships in a lower-middle-class family, about young people trying to find their way, about missteps and successes, sexual awakening and minor transgressions. It is a ground-level view of three cities at a very particular time in a nation’s history. And it is an enquiry into what it takes to be an artist, and whether the effort is worth it . . . One of this narrative’s achievements is that it is wonderfully fluid even though the structure is really very intricate’—Jai Arjun Singh, Open

‘Riveting reading . . . Ashk is fortunate to have found Daisy Rockwell as his translator for not only does she have the stamina and tenacity to take on this mammoth cycle of novels but also seems to have a rare devotion for Ashk himself . . . Falling Walls becomes compelling reading simply because it transcends the personal and particular. In its slow unfurling of a mind looking to expand its horizon, in its insistent exploration of the darkest recesses of the human heart it no longer remains just the story of one young man. Also, given its richly textured narrative, its setting in provincial Punjab and its depiction of a Punjabi youth struggling to find his feet in a literary world dominated by Urdu writers, it chronicles a world located at the cusp of change . . . Ashk is nothing if not brutally honest in his portrayal of all that afflicts a young man raised by a devout mother and depraved father in an atmosphere of utter suppression of the most natural of human impulses. What emerges, then, from a reading of Falling Walls . . . is the arresting portrait of a young man wanting to become an artist’—Rakhshanda Jalil, Wire.in

‘[Falling Walls is] a 1947 novel by one of Hindi literature’s best-known names, Upendranath Ashk, [and] offers an intimate portrait of lower-middle-class life in the 1930s. From the back lanes of Lahore and Jalandhar to Shimla’s Scandal Point, Falling Walls is also about the hurdles an aspiring writer has to overcome to fulfil his ambitions. The six-volume novel cycle [Falling Walls] earned the author comparisons to French novelist and critic Marcel Proust. Ashk was the recipient of numerous prizes and awards during his lifetime for his masterful portrayal, by turns humorous and remarkably profound, of the everyday lives of ordinary people’—Economic Times

‘[A] superbly crafted and meticulously detailed, larger-than-life novel . . . Magnificent . . . Falling Walls will not fail to impress. It is as if an entire microcosm of old town lanes, teeming with people of all kinds suddenly comes alive . . . Ashk writes with a clear hand and is served well by Daisy Rockwell as she recreates a compelling narrative’—Dawn

‘Falling Walls is a keenly modern novel . . . Rockwell’s immense research shows in her deft translation, where nothing jars as she effortlessly conveys the local colour . . . She moves the Hindi text towards the English reader but knows how far it can be pushed from its terrain . . . This novel must be read, not least for its description of our forgotten literary cultures and a subaltern history of pre-Independence times’—The Hindu Business Line

‘In the world of Hindi literature, Upendranath Ashk was a towering figure . . . best known for his six-volume novel cycle [Falling Walls]’—The Hindu

Praise for Hats and Doctors

‘Hats and Doctors offers the English reader the first proper glimpse of Ashk’s very particular sensibility: profound yet light-hearted, satirical yet deeply engaged. He unravels the ironies of his protagonists’ lives with a wry humour: sharp as a scalpel, yet somehow understated’—Mint

‘Hats and Doctors offers readers in English a taste of Ashk’s short fiction, in which complex themes like marriage, mortality and the colonial legacy are rendered with a lightness of touch’—The Hindu

My novel is a mirror of life and it reflects, while it journeys down the highway, the blue skies and the mire in the road below.

—Stendhal

My footprints are still restless here

I’ve wandered these same paths for years

To Life’s intricate paths

Author’s Preface

The characters in my novel In the City a Mirror Wandering have inhabited my mind for years. One could even say they had actually become an obstacle to my writing. Whenever I thought of writing a new novel, they always blocked my path. I am relieved now to feel finally lighter for having put them down on paper.

I first started writing the novel in 1957. That year, I had gone to Dalhousie in hopes of writing the whole novel there. But I was so captivated by the beauty of the place that I ended up just writing poems instead. All the same, once that mood ran out, I again put my hand to the task and wrote five chapters. But for the next three years, I couldn’t get any further, no matter how hard I tried. Every year I attempted to complete the book, but I was only able to write seven more chapters.

I was so distressed by the slow pace of the novel that when I became the chairman of the Assam Hindi Sammelan in 1961, and went to Tinsukia (Assam), I took the manuscript along with me. I had thought that after my tour in Assam, I’d stop in Kalimpong and not return until I’d finished the novel. But I did not find the climate in Assam salutary. I fell ill in Shillong and had a fever by the time I reached Kalimpong. My wife wanted me to return and recuperate, then go elsewhere to write. But I stayed on and, despite my illness, finished the book in one and three-quarters months. I couldn’t sleep at night for coughing, so I slept by day and wrote all night. Although my health deteriorated even further due to this pig-headedness and my old TB grew a bit active again, I have no regrets. I have complete faith that had I returned without finishing the book, I wouldn’t have been able to write it for many years more and that this would have become a source of relentless anxiety.

But was it right to undertake so great a risk for the depiction of such a mean, mediocre, lower-middle-class life? It’s possible my critics will read it and ask this very question with sarcasm and disdain. I have no answer for them. I can only describe my own compulsion to write it.

I am heartily grateful to my comrades Surendra Pal, Virendranath Mandal and Kaushalya, who helped me greatly in preparing the press copy. I regret that because of my current ill health, I was not able to do as much work on it as I usually do. There must be some errors remaining. I hope that sympathetic readers, on hearing of my plight, will not judge the book for any small errors. As always, I welcome their suggestions.

25 March 1963

To the reader who expects every work of art to teach him something, I submit that a good work of art does not teach anything directly, but that those inclined to learn will learn a great deal. There’s a saying in Punjabi:

Ikkanāñ nūñ ditti rabb ne

Ikkanāñ ne sikkh layi

Ikkanāñ nūñ jo na āyi

Jyūñ patthar būnd payi

That is, there’s one type of person who’s born already knowing everything from God; another learns (by observation or study); and then there’s the third type, off whose mind knowledge rolls like drops of water from a rock.

In order to gain something from another person’s impressions and experiences, one must keep an open mind. Those who have been born knowing everything and those who can’t learn anything won’t get much out of this novel. This novel is intended only for the middle group (of which the writer considers himself a member as well), and he’s found that most readers fall into this category. It is into their hands that he hesitantly presents this book.

Translator’s Introduction

But the question is, in this age of struggle, for whom does the storyteller write? Does he write for the wealthy and aristocratic writers or critics of today, who now take the place of Kalidas’s maharajas, or does he write for the thousands of people engaged in struggles just like himself? Kalidas and his contemporaries lived under the patronage of rajas and maharajas, they created literature solely for the enjoyment of their masters, and what would be the use of sickness, sorrow, poverty, the tiny, aggravating details of life that leave a bitter taste in one’s mouth—those utterly ordinary, negligible events—to a raja? Some of our critics even see themselves as the rajas and hold similar expectations of the writer. But if the writer doesn’t write for them, if he writes for the thousands of other mud-smeared souls, like himself, then clearly he won’t show them the beauty of the lotus but all the other items in the lotus tank: the spreading roots, the mud, the slime, the weeds and all the other matter the writer wishes to clean from the tank—all of it—all such items are responsible for the spread of countless germs of illness and filth, whether five lotuses happen to bloom there or ten.

—Upendranath Ashk, from his Introduction to Falling Walls

I. The Muck in the Lotus Pond

In Falling Walls, the first volume of a planned series of novels covering five years in the life of his autobiographical protagonist, Chetan, Upendranath Ashk made clear his intent of writing about the not-so-pretty aspects of lower-middle-class life in Punjab. He was recording not the lovely lotus as it floats in the tank, but all the other muck and slime that can be found beneath. He was writing about real life and for ordinary readers. In this second volume of his epic tale of a young man climbing out of the metaphorical pond-scum of his existence towards the light of aesthetic expression and worldly success, he embraces this goal with renewed vigour. In the City a Mirror Wandering, first published in 1963—sixteen years after Falling Walls—takes the modernist ‘pattern’, as Ashk called it, of the epic novel contained within a single day made famous by Virginia Woolf in Mrs Dalloway, and James Joyce in Ulysses, and drags it through the literal muck of the Jalandhar streets one grimy monsoon day, stinting nothing in airing every bit of dirty laundry that caught its writer’s eye.

In these provincial city streets, we meet goondas, halfwits, bullies, frauds, drunks and misogynists of every stripe. Chetan leaves his family home, and his sleepy wife, Chanda, early in the morning, still smarting from the recent marriage of the woman he loved, his wife’s first cousin Neela, to a middle-aged accountant from Rangoon. He sets out on an aimless tour of the city streets in search of some sort of emotional and spiritual comfort. He wants friendly companionship, or sympathy, or at least a sense that he has done something with his life of which he can be proud. Instead, he is greeted at every turn not only by crude humour and bullying, but also by neighbourhood gossip about the fresh accomplishment of his former classmate Amichand, who has just qualified to become a deputy commissioner. This rankles especially because Chetan had recently encountered Amichand in Shimla, and been greeted superciliously, as though Amichand had already reached such a high level that Chetan was now far beneath him. In Chetan’s mind, Amichand is nothing but a crammer—he had possessed no extraordinary talents or intelligence that would have suggested his rise to such heights. And yet ‘Amichand’—not ‘Chetan’—is the name on everyone’s lips.

This epic journey of revulsion and despair ends where it began, by the side of the sleeping Chanda, in a small rooftop room in his family home. He had gone on a manly quest beyond the hearth, and walked among his fellowmen, yet found everyone and everything profoundly wanting. It is only deep in the night, when he raises the flame of the low-burning lamp by the bedside to gaze at his wife that he realizes that all the love, compassion and respect he seeks is here, in the woman he had dismissively abandoned early that morning. This realization is touchingly poignant, but it may also seem absurd to the contemporary reader. Is this what it takes for a man to recognize the humanity in his wife?

In the City a Mirror Wandering is hardly a feminist tale, despite the careful portraits of the callous abuse of women that Ashk documents. But it can be read as a finely wrought portrayal of the inhumanity of men, not just towards women, but also towards one another, in a cultural context plagued by generations of poverty, illiteracy and superstition. The walls that Ashk hoped to see falling are the barriers to progress posed by an entrenched culture of urban want, and one such barrier is that which divides men and women, rendering loving and respectful communication nearly impossible (as well as creating an epidemic of sexually transmitted disease

s). Chetan’s realization that he can open up emotionally to his wife is a revelation in an environment where woman are seen entirely from a sexual and reproductive standpoint and their worth is measured in terms of ownership by their husbands and symbolic ownership by their caste-communities.

This is nowhere more apparent than in the final conflagration of the novel, a mini-epic battle between the neighbourhood’s Khatris and Brahmins over the beating of Bhago, a Khatri woman who had run off with a Brahmin. As Bhago lies bleeding on a charpoy in the middle of the mohalla, there is less concern for her comfort and well-being than for exacting justice against the assailant, her caste-mate and Amichand’s brother Amirchand, newly emboldened by his brother’s triumph. Indeed, it is decided that she should be carried on the charpoy to the local police station to be presented as evidence, and only after that should her grievous head wounds be tended by the local hakim, who is present throughout. The history of male literature is littered with women desperately needing medical attention while men do important things (think of Fantine, delirious with fever, and abandoned for many pages, while Jean Valjean embarks on a quest relating to his identity in Les Misérables), but it is always hard to bear.

In Hindi, the verb for ‘hit’ or ‘beat’ is the same as the one for ‘kill’—mārnā. This ambiguity is borne out throughout the scene, with reports coming in that Amirchand has beaten Bhago, but it is unclear until the end if he has beaten her to death (jān se). Indeed, her condition is still unclear when the conflagration devolves into a round of virile wrestling between Chetan’s brother Parasuram and his friend Debu under the referee-ship of Chetan’s father. What was really at stake was the relative masculinity and power of the two communities, and Chetan’s father is only reminded of Bhago’s plight when he’s about to take the two wrestlers for their reward of fresh milk at the sweet shop.

In the City a Mirror Wandering

In the City a Mirror Wandering